Reprinted from The Times Eureka Magazine Issue 6 March 2010.

By Paul Rose

A Terrible Beauty: Edward Wilson in Antarctica 1902 – 1912

Edward Wilson, who died with Scott on their return from the South Pole, was a brave explorer and an inspiring artist.

Polar Scientists. A Special Breed;

Polar Scientists. A Special Breed;

I have spent most of my working life in Polar and other remote regions with the special breed of people known as field scientists. We can all imagine scientists pursuing their work with energy and passion, but until you have lived, travelled, dug, lifted, drilled, climbed, skied, swam and shivered with them it is hard to understand just what a special breed they truly are. I often say that field scientists are impervious to cold, heat, bad food and general discomfort.

Along with superhuman resilience to difficult conditions their other defining character trait is artistry. To interpret discoveries in the field into a workable scientific hypothesis always feels like a great leap to me and it can only be done with a finely tuned combination of science rigour and art.

All this while striving to maintain the exacting standards set up and agreed at the start of the project in a nice warm laboratory.

Edward Wilson;

Edward Wilson was Captain Scott’s right-hand man. He was on both of Scott’s Antarctica expeditions: On the 1901 – 1904 Discovery expedition he was the Junior Surgeon and Zoologist and along with Scott and Ernest Shackleton he set a new Furthest South. On the 1910 – 1913 Terra Nova expedition he was the Chief of Scientific Staff. He reached the South Pole with Scott, Oates, Bowers and Evans.

They all died on the return journey; Oates and Evans died whilst travelling and Scott, Bowers and Wilson were found in their tent only 11 miles from their main depot and safety.

The Discovery search party who had gone to find them spotted only a few inches of the tent sticking up from the accumulated snow. After digging out the entrance and bracing themselves for what lay within, they opened the entrance to find Scott laying between Wilson and Bowers his arm flung over Wilson. The parties notes report;

The Discovery search party who had gone to find them spotted only a few inches of the tent sticking up from the accumulated snow. After digging out the entrance and bracing themselves for what lay within, they opened the entrance to find Scott laying between Wilson and Bowers his arm flung over Wilson. The parties notes report;

“Dr Wilson was sitting in a half reclining position with his back against the inside of the tent facing us as we entered. On his features were traces of a sweet smile and he looked exactly as if he were about to wake from a sound sleep. I had often seen the same look on his face in the morning as he awakened as he was of the most cheerful disposition. The look struck us all to the heart and we stood silent in the presence of death”.

Before the tent was collapsed around the men vital diaries and records were gathered including Wilson’s tiny New Testament which was removed from his pocket. I have this in my hand now as I study his watercolours here at the Royal Geographical Society, London.

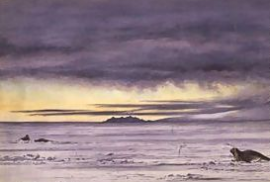

There are thirteen works on the table and immediately I am drawn to “Looking North in McMurdo Strait, midday 26 July 1902, with Seal” and “Mount Erebus from Hut Point March 1911” because only a few weeks ago I stood at the same spot Wilson did to paint these. My circumstances were very different from his: I was about to fly into Antarctica’s Dry Valleys and had walked from McMurdo to the Discovery Hut. This was the base for the Discovery expedition. It is in remarkably good condition and even though it now stands in the shadow of the large US science base, McMurdo, it retains a sense of purpose and vitality that is impossible to ignore.

Thinking back to my time at the hut and with Wilson’s New Testament in my hand I am overwhelmed by the power and sense of his work. Like many people with polar interests I have been familiar with Wilson’s watercolours, but it’s one thing to see reproductions in books or online and quite another to stand in front of the originals.

Thinking back to my time at the hut and with Wilson’s New Testament in my hand I am overwhelmed by the power and sense of his work. Like many people with polar interests I have been familiar with Wilson’s watercolours, but it’s one thing to see reproductions in books or online and quite another to stand in front of the originals.

The works are beautiful, superbly accurate and bring Antarctica to life. I expected that, but what did surprise me is that they are so delicate. Wilson was a very strong, athletic character. He was a powerful performer in the field and a key member of the winter journey to Cape Crozier as recorded in the iconic “The Worst Journey in the World” by Cherry-Garrard. This was a mid-winter epic journey of 134 miles in desperate conditions to collect Emperor Penguin eggs. But for Wilson’s strength the party would have perished. On another occasion Wilson was suffering from snow-blindness and had blindfolded himself to help relieve the pain, but he still pulled his full weight on the sledge harness as he was led by Scott and had the scenery described to him as they moved. This powerful man who’s vitality seems to leap out from the expedition images produced beautifully delicate watercolours and sketches.

Edward Wilson was passionate about sharing his Antarctic with us all. I have completed twelve Antarctic seasons and my brief time with his work has greatly enhanced and changed my perception of Antarctica. I ask you, encourage you, implore you to visit the exhibition and see the works for yourself.